Author: alasdair.geo (Page 10 of 13)

Max elevation: 0 m

Total climbing: 0 m

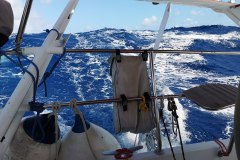

We motored SE towards Las Perlas, amazed at the number of ships at anchor waiting transit, and also the large number of tuna boats (Barracuda would pass close to some of these massive fleets en route to the Marquesas). Our first week in the Pacific was to be fairly easy, as there was not a great deal of wind. We motored into the gap between Chapera and Mogo Mogo islands in mid-afternoon. We tucked in close to Chapera to get out of the tide and had a swim in the clear water. We then explored the beaches on both islands, which had beautiful sand, with nobody on them. (Chapera is used for the “Survivor” TV series)

The next day we started out under sail, but turned on the engine after a few hours due to the lack of wind. Our anchorage for the night was on the southern end of San Jose Island. We were out of the prevailing wind, but there was a good swell from the south, with waves crashing onto the beach. We had read about a cave that you could take the dinghy into, but the swell made this impossible. Later in the evening we had a visit from a friendly pelican.

We had a good sail over to the anchorage at Playa de Cacique, on the south side of Isla del Rey. Our plan was to explore the Rio Cacique. We had an exciting ride with the breakers over the bar at the river mouth and then motored slowly upstream. This was real jungle exploration through the mangrove swamp, keeping to the channel, but still having to work our way round fallen branches. Occasionally there would be a loud crash from some animal moving through the mangroves. We stopped the engine and drifted back down stream on the falling tide. There was another exciting moment getting back over the bar and then it was time for a swim and drinks.

There was an early start on Saturday morning, motoring all the way up the east side of the island. We spotted a telecoms tower above San Miguel on the north coast, so had a swift change of direction to enable us to access the internet and emails while we had lunch at anchor. In the afternoon the Angus and Kate fishing competition finally resulted in the capture of a large bonito. Angus spotted the fish on Kates’s line, so it was agreed to split the honours. We headed into a sheltered bay on Casaya Island. The entrance (on the chart) appeared to be a straight run in from the east, but as we got nearer, we could see the reef extending further south. Google Earth confirmed the extent of the reef, and we headed in, pulling up the centreboard to tuck in beside Ampon Island, and out of the swell. We woke to find a fishing net wrapped round both anchor chain and rudder. The fishermen were about a kilometre away, and slowly approached, hauling in their net. They quickly retrieved their net and moved on, accompanied by lots of pelicans. The men had caught at least one large tuna for their efforts. It was low tide (we had 50cm under the hull), and the limits of the reef were clear as we headed back out and turned north. We motored back to our first anchorage off Chapera for another snorkel, and then continued to Contadora Island, where there was to be a cocktail reception and dinner for the World ARC fleet. The fleet would be setting off for the Galapagos in a couple of days, and then on to the South Pacific Islands. Barracuda would be setting their own, much slower, pace. It was time to say goodbye to all the friends we had made. The next day we motored back to Panama City, practising our sextant work on the way, and discovering that if it’s a bit hazy, it’s impossible to differentiate sea from sky! Good news – the repaired mainsail was waiting for us. A night in the marina, and I then jumped in a taxi for my flight back to the UK.

Postscript

The World ARC fleet visited the Galapagos and were on their way to the Marquesas (French Polynesia) when the quarantine rules came into force. Most of the yachts ended up in Tahiti, with the crews flying home, and World ARC cancelled and delayed for a year; one US yacht went to Hawaii. Graham and Kate were in the middle of a crew change in the Galapagos when lock down started. Angus got home OK, one new crew member got as far as Peru before having to return to the UK, another couple did get to the boat, and so Kate decided to stay rather than attempt to fly home. After weeks of lock down in the Galapagos they sailed for the Marquesas, having been assured that they would be allowed entry. They arrived there just as the quarantine restrictions were lifted, and are now working their way through the Marquesas and Tuamotu Islands, before heading for Tahiti.

Max elevation: 55 m

Total climbing: 475 m

Panama crossing 1st and 2nd February

With Angus having arrived, we had also picked up another ARC sailor to give us our required quota of crew. We arrived at the rendezvous point just outside Shelter Bay marina and waited for our “advisor” to arrive. Each yacht in our nest would have an advisor on board, who would tell us what to do and when. The advisors all work for the Panama Canal Authority, and working as an advisor on board a yacht is done outside their normal work hours. It’s also a requirement if they are to become pilots. (Working for the PCA certainly seems to be high up on everyone’s job list in Panama). A short while later, we saw a pilot boat heading our way, we each took on board an advisor, and started making our way down the channel towards the first lock.

We’d all been reading up about the canal on Google, but Angus arrived on board with “The Path Between the Seas” by David McCullough. He was now able to answer all our questions about the history (1870-1914) and structure of the canal, although he pointed out that despite having read three-quarters of this 700-page book, nobody had yet started any excavation! The French had tried and failed miserably; the Americans came along and realised that yellow fever was killing all the workers, and once they eradicated it, construction (and completion) became a possibility.

We motored on towards the Gatun Locks, where three locks would lift us up to Gatun Lake. The Chagres River, which I saw on my trip to the fort, had been dammed to create the enormous lake, provide a crossing across the isthmus, and also water to operate the locks. There are parallel locks, used by ships up to Panamax size; the new, bigger set of locks allow the neoPanamax ships through. As we approached the locks we made up our nest of three, with a catamaran in the middle, and one yacht to port, and Barracuda to starboard. Most of the steering is done by the central yacht, with the others providing back-up power where necessary. As we entered the lock, heaving lines came down to us, we attached our mooring lines, and we motored forward, with the line handlers on the dock walking forward with the lines. As we approached our position in the lock, the line handlers pulled the mooring lines up to their level, secured them, and we then controlled the lines from the boat. (Ships are controlled by small railway engines handling their lines, and possibly a tug on the stern as well). We had one ship in the lock ahead of us, which can affect the flow of the water into the lock. The water certainly comes in quickly, so it was vital to have turns round the cleat as you can have the weight of three boats on the line. As we rose up it was necessary to take in the slack, taking care not to get hands anywhere between the line and the cleat. First lock done, two more to go! We were soon through the locks and out onto Gatun Lake.

We would be spending the night tied to a buoy in the lake and completing our transit in the morning. The evening was spent socialising on board the catamaran Remedy; three bedrooms (it would be rude to call them cabins), all with en-suite. The kitchen had a microwave, coffee machine, freezer, etc, and there was air conditioning throughout. The kitchen/diner was huge, and the lounge area next door even bigger. You obviously need a large battery supply to run all of this, and then a decent generator, and lots of fuel… (This catamaran was one of the smaller ones taking part in the ARC world cruise). As one cat owner said to us “We’ve tacked a dozen times in three years of sailing. If you’re going downwind most of the time, why not get a catamaran?”

All the yachts rolled very heavily at times during the night because of the passing ships, enough that one of the fender lines snapped. We spotted it on the shore in the morning, and had time to retrieve it in the dinghy before the advisors arrived. We were soon on our way across Gatun Lake, then leaving it via the Gamboa Reach. We spent most of this, and all the way to the locks, very close to a very large container ship. At times she would pull away from us, other times we would catch up and overtake as they slowed for a passing manoeuvre. Ships can only pass each other on the straights, and there is also a 6 knot maximum closing speed if one of the ships has dangerous cargo. We were motoring along the very edge of the channel, but were still within 30m of these monsters. Then it was into the Culebra (formerly Gaillard) Cut; 32 years of digging had taken place here, with numerous landslides. As we approached the first of the down locks, it was time to raft back up into our nest.

The line handlers on the land know their job well. I spotted mine, as we motored into the lock, crossing the railway, walking over into a hut, and having a conversation as he paid out his line. He then started gathering up the line as he speeded up to retake his position! This time we had a huge three masted cruise ship in the locks with us. We nearly had an incident as the aft port line on the other yacht was caught as the level in the lock dropped. Luckily, a knife wasn’t needed, but it took four people to take the strain and free the line. The nest was swinging about in the lock before it was brought back under control with the combined engines of all yachts and adjustment of all the lines.

After the Pedro Miguel locks it was a short motor across the Miraflores Lake before the final two Miraflores Locks. There was a huge crowd watching us from the visitor centre. They all thought we were waving at them, when we were actually waving to friends and family watching us via the webcam mounted on the same building. Out of the locks, untie our nest, drop off the advisor, motor under the Bridge of the Americas, and we were officially in the Pacific! There was then a short motor to the La Playita marina, located at the end of the breakwater off Panama City. A few days here would allow us to reprovision; there was not going to be another good opportunity for Barracuda’s next legs to the Galapagos and then on to the Marquesas in French Polynesia.

The Pacific would bring an entirely new experience to many of the ARC skippers and crews – tides. They had come from the Caribbean with zero tide, to a 6m tidal range!

Max elevation: 84 m

Total climbing: 325 m

Santa Marta to Shelter Bay 22nd to 29th January

Another briefing (and prize-giving) organised by the World ARC team and we were nearly ready for departure on the next leg of our trip. This was to take us to the northern entrance of the Panama Canal, via the San Blas Islands off the NE coast of Panama. Graham completed the paperwork (the most of any country he had been in), retrieved our passports, and after some final shopping we were ready to go.

After days of non-stop 30 knots wind from the east, the wind had dropped during our stay, and the morning of the 22nd saw us with a light wind from the west! The choice of tack was therefore starboard towards the Colombian coast, or port out to sea and hopefully better winds. The view back to land (and the plotter) showed that we were actually heading north at best, with about 3 knots of current against us from the west. We, and everyone else, finally put the motor on and dropped sail. At best, we made 4 knots over the ground throughout the night, watching various shore lights slowly disappearing into the distance. The morning brought wind from astern, so it was up with Parasailor. We also finally managed to catch a decent sized tuna, which gave us several meals. Unfortunately, the lack of wind meant that we would have a day less in the San Blas Islands, if and when we arrived. The wind finally went more on the beam, and speed picked up. With the wind dropping on the third day, it was time to turn the motor back on to try and reach anchorage before nightfall. It was not to be, and we passed through the wide gap between some islands in the dark.

The entrance to the anchorage was a narrow passage between some reefs and we agreed with two other yachts that we would raise our keel and lead them in, reporting on depths. It was at this moment that our echo sounder decided to stop working. Motoring in through the reefs, in darkness, with no echo sounder was a definite no, and we debated whether we should head back out to sea and wait for daylight. Instead, all agreed that we would now be the third boat in the convoy, following very close behind the second yacht. One of the earlier arrivals had provided some waypoints and we kept exactly on the plotted track. It was a nervous fifteen minutes before the lead yacht announced that their depth soundings were increasing, and that we were now safely in the anchorage.

Morning showed us that we were in a picture-perfect anchorage, surrounded by small islands covered in palm trees, with the surf breaking on the reef to the north, and a distant view of mountains to the south. We had some early visitors as a dugout canoe arrived, wanting to sell us some of the locally embroidered “molas”. A second canoe arrived with lobsters, so dinner was soon sorted. The San Blas Islands, properly called Guna Yala, are home to the Kuna people, and are semi-autonomous. Most of the islands are uninhabited or have a few dwellings, while some are completely covered by shacks and houses. The elevation of the islands is only a couple of metres above sea level, and they are certain to be engulfed by sea level rises. Ecotourism is now bringing money to the islands, and one of the islands beside us had a number of huts for the genuine “desert island” experience. We visited one island to see molas being made (see photos) and enjoyed a number of swims and snorkels in the beautiful water. We also did some boat maintenance; the biggest job being checking all the wiring connections before deciding that it was a problem with the depth sensor. Luckily, one of the other boats had a spare, and we had sufficient cabling to install the new sensor and get it working.

We then headed over to the island of Porvenir, where we would officially be checked into Panama. As we lifted the anchor that morning we had noticed a number of rain storms, and when we saw one coming our way, we suggested to the boat departing with us that we delay while the rain passed. They refused, so we raised anchor and motored out. As Graham and I, in t-shirts and shorts, got soaked to the skin by the rain, we looked over at the other boat to see them in full oilskins!

Porvenir has an airstrip, a hotel, and a passport office. The neighbouring island seemed to have buildings covering every possible centimetre. At anchor that evening, we heard splashing and went on deck to investigate. There were about a dozen dolphins chasing a large shoal of fish. We got out the torch, and could actually follow individual dolphins as they raced through the water, doing u-turns as the fish tried to escape. An amazing sight. There was time to visit one more anchorage in these amazing islands before we set sail for Shelter Bay marina to learn about our canal crossing.

We left these beautiful islands at midday on the 28th for our overnight sail as we wanted to be certain of getting through the shipping at the entrance to the canal in daylight. Three other yachts left at the same time, partly for protection, as this stretch of the coast has seen some piracy recently, so we all kept well offshore and were relieved as we turned south west for the canal. As we approached the breakwater we counted over 50 ships at anchor, while others passed down the main channel, either to the canal or to the port of Colon. Ahead, we could see the new bridge over the entrance to the Panama Canal and the two breakwaters at the entrance to the bay. At the breakwater, it was a sharp right turn to follow it to the Shelter Bay marina, where we were to be based for a few days. Barracuda had finally left the Atlantic Ocean.

Graham’s brother, Angus, joined us bright and early the next morning, having flown in to Panama City and then taxied across the isthmus. He would be staying with Barracuda for a few weeks and getting off in the Galapagos. Our time in Shelter Bay was fairly busy; washing to do, a full rig inspection by a qualified rigger, and the main was put in for some repairs. The sailmaker was busy and agreed that we would pick up the main in Panama City, a couple of days after our arrival there. An ARC briefing told us what to expect during the canal trip, and which “nest” of three boats we would be in. We were officially measured and given Barracuda’s certificate and transit number. If you are over 60 feet, you get to transit by yourself, with a pilot. Otherwise, you travel in a nest (raft) of three yachts, each with an advisor on board. Although the nest only needs four mooring lines, each yacht must have four in case the nest comes apart. You must also have four crew plus helm. The mooring lines were provided by ARC, along with some equally big fenders. There were about 40 ARC yachts going through the canal over a period of about four days; some crew made the trip to Panama City, then came back to help short-handed crews.

I had time to visit Fort San Lorenzo, located at the mouth of the Chagres River, and the original export route for South American gold, along with Portobelo to the east. I hitched a ride through the jungle and arrived at a spectacular location, above the river, with great views out to sea. The original fort had been destroyed Captain Morgan, rebuilt, then destroyed by Francis Drake.

Panama was coming to the end of the dry season and so dates for transiting the canal were changing almost daily. Finally, we were told that we would be leaving the following evening. The next morning, at about 9am, we got the radio message, “you are leaving at midday”, so there was a final rush of preparation before motoring out into the bay and waiting for our advisors to arrive.

Max elevation: 9166 m

Total climbing: 10840 m

Max elevation: 69 m

Total climbing: 343 m

On 11th January, the gun sounded, we crossed the line, and set sail for Santa Marta, Colombia. The initial course took us down the west coast of St Lucia, rounding a mark, and then heading direct to Santa Marta. Even within the lee of the island it was fairly windy, and we had to shorten sail even more as we reached the mark and saw a squall approaching. As we headed further west out of the wind shadow the wind increased up to about 25 knots; throughout the entire leg the wind never dropped below this. It was above 30 knots, with some line squalls to about 45 knots. We steered using the Wind Pilot which has two big advantages; no-one needs to helm, and it doesn’t need any power. The slight disadvantage was that it would steer us slightly to windward, about one mile to windward for every ten downwind.

The three of us stood night watches by ourselves, with three hours on watch. The watches ran from 9pm to 6am. In European waters, 3am to 6am is usually quite rewarding as you get to see the sun rise. In the tropics, sunrise was about 6:45am, so even this watch was in darkness. Time on watch was spent reading, watching the stars, and keeping an eye out for line squalls.

Line squalls are a hazard of sailing in the tropics. During the day it is easy to see a line of clouds approaching and if you are near any one cloud you can expect a sudden increase in wind speed (we recorded 45 knots at times), possibly pouring rain, and then it is over as quickly as it arrived. At night, if the stars vanished it was time to turn on the radar, watch the direction of the clouds, and call for help to decrease sail if a squall was going to hit. Bizarrely, several times during the day we watched a squall go past a few hundred metres from the boat with wind and rain while we sailed on completely unaffected.

Kate did an excellent job of preparing lunch and dinner (stored in a “Mr D’s thermal cooker”) to minimise time spent below until we got our sea legs. I spent the first night feeling a bit queasy, but the excellent Joy-Rides Travel Sickness tablets stopped the nausea, and I was able to dispense with the tablets during the second day.

We started the first day under main, with the genoa goose-winged. The second day saw us drop the main and put up a staysail to port, with the genoa poled out to starboard. This allowed us to point more downwind than we had managed on the first day. The waves had now built up to about 3-4 metres and we were regularly surfing down waves, helped by raising the keel, thus turning Barracuda into a planing dinghy!

To control the sails, we had about 16 different sheets rigged. Each day we had a full topsides inspection, checking sheets for any chaffing, inspecting the rigging, and tightening any bolts on the wind pilot which might have worked loose.

We saw the mountains of South America appear, and as the wind had dropped, we went back to full mainsail, along with the poled out genoa in order to catch (we hoped) the boat ahead of us. We had been warned about the strong winds off Santa Marta, and as we approached the wind started to increase; we crossed the finish line on 16th January with three reefs in the main and a few feet of genoa.

It was even very windy in the marina, leading to challenging berthing conditions, with several people on the pontoon and a RIB to help us dock. (This wind didn’t drop for the first two days we were there, leaving a fine layer of sand everywhere below.)

We arrived to hear the music blasting out from the beach next door; it was still holiday time in Colombia, and the partying continued all day and into the night.

The wildlife that we saw was fairly limited; a few pilot whales, lots of dolphins, and every morning dead flying fish on the deck. There was the occasional bird sighting.

Max elevation: 114 m

Total climbing: 856 m

Some film of Barracuda surfing the waves:

A trip from St Lucia, via Colombia and the Panama Canal, to the Pacific

My friends Graham and Kate left Scotland on their Ovni 395, Barracuda of Islay, in 2017. They sailed down to the Azores, crossing with ARC during winter 2017/2018. (The World Cruising Club organises lots of different rallies, with the ARC across the Atlantic to the Caribbean being the most popular.) After finishing in St Lucia, they sailed on up through the Caribbean and the east coast of the USA before lifting the boat out for the hurricane season in mid-May in Deltaville, Virginia.

In October they were back on board, and motored down the ICW (IntraCoastal Waterway) to Florida. They then slogged against wind and tide heading SE, before finally getting more of the trade winds near the BVI and making their way to Grenada, arriving in April 2019. The boat was lifted out, and put back in the water in early December, then sailed up to St Lucia. A week later, I joined them for the first leg of their round the world trip, from St Lucia to Panama, stopping in Colombia on the way. Graham and Kate sail the ocean passages with one or two extra crew, the shorter island hops by themselves, and their Ovni 395 is set up as an “expedition” boat; aluminium hull, lifting keel, lots of spares, a serious first aid kit including an AED, and electricity and water generation. The Ovni 395 is probably the smallest of this class of boat and we spent many evenings discussing what would be the ideal boat in terms of size, onboard kit, and sail configuration.

We were starting in the World ARC Rally 2020, a fifteen month, 30000 mile trip for the full entrants. We, however, were only taking part as far as Panama City as Graham and Kate want to take a lot longer on their circumnavigation. The reason for joining World ARC on this relatively short leg was to guarantee a date for going through the Panama Canal, of which more later.

I joined the yacht, and was immediately immersed in the full round of provisioning, rig checking, and all those other small jobs on boats that seem to be never-ending. Kate has got food and liquid provisioning well organised on her spreadsheet. Another spreadsheet calculates the electricity consumption, our likely production from solar panels and the wind generator, the amount of time we would need to run the engine to make up any shortfall, and how much fuel that would leave us for any motoring, and what that range would be. We left with every possible space full of spare water in case the water maker failed, and eight spare jerry cans of fuel on the deck.

A folder on the yacht had all the checklists, such as pre-departure and daily, and other information such as what to do if we lost the rudder, or “black ship” – an entire loss of electricity.

All the ARC yachts are provided with YB trackers so that people can follow their progress. We also had a Garmin inReach GPS which can also send and receive messages, the main GPS on the navigation system, and of course everyone’s mobile phones have inbuilt GPS. There was also a sextant and all the tables for our part of the world, which we used occasionally for practice. Communication was via VHF, SSB radio giving a potential range of hundreds, if not thousands of miles, and a satellite phone. The ARC has a twice daily fleet chat on the SSB, and we could also download the weather as grib files.

There’s radar on the yacht; the main use was at night when trying to determine whether a line squall was coming our way. Each lifejacket had a personal AIS installed. Surfing down 4m waves at ten knots meant that it would take quite a while to get back (especially against 30knots of wind), so the main objective was to make sure you never went over the side.

The big day arrived, with a “race” start. As most of the yachts had never raced before (in fact I was surprised at the limited sailing some of the people had done), we approached the start line cautiously, keeping well away from other yachts. The gun sounded, we crossed the line, and set sail for Santa Marta, Colombia.

The stages of the journey can be found below.

Max elevation: 9166 m

Total climbing: 12864 m

A day in Spa.